Compiled by Martin Davis © 2010- 2017

Click to enlarge photos

My grandfather and grandmother on my mother's side lived in the town of Kamenets-Podolsk (Western

Ukraine). My grandfather’s name was Haim Gershkovich Altman and my grandmother’s name was Haya-

Surah Altman (I have no information about her maiden name). My grandfather was born some time in 1880,

and my grandmother in 1885. They were both born in Kamenets-Podolsk and lived there all their lives.

Kamenets-Podolsk was a very beautiful town on the bank of the river Smotrich. Many Jewish people lived

there. They were involved in commerce and various trades: shoemaking, dressmaking, leather tanning, etc.

There was a nice synagogue there, too.

My grandparents had a house of their own, a small wooden house with outdoor plumbing. The house had

four rooms and a veranda. There also was a Russian oven that served for both cooking and heating. My

grandfather and grandmother were good housekeepers. They had an orchard and a vegetable garden

around the house, and they kept chicken, ducks, geese, goats and a cow. My mother told me that when it

got cold in winter they brought their goats into the house. They always had enough milk. My grandmother

made sour cream and baked milk (ryazhenka) in her oven and sold these at the market. She also sold

eggs. My mother told me that they always had enough food, although my grandmother and my mother had

to work hard for it. People from the neighbouring villages often stayed at my grandparents’ house. They

came to sell their fruit and vegetables at the market and buy whatever they needed. The Jewish and

Ukrainian people got along very well. Many Ukrainians spoke Yiddish fluently.

My grandparents were very religious. My grandfather attended synagogue every morning and then went to

work. He worked for a Ukrainian grain dealer, handling his grain. He was a very good employee, and his

boss always gave him grain in addition to his wages, so they always had a lot of bread and baked goods at

home. In 1909 Munya, my mother’s older brother, was born.

My mother attended secondary school for eight years and also attended music school. There was a piano

at my grandfather’s house. Mother had a very good sense of music and used to sing very well. She had

quite a few friends – both Russian and Jewish. Her Jewish friends Genecka and Donia (I don’t know their

last names) were not evacuated during the war and were killed. Donia died in Lvov and Genechka – in

Kamenets-Podolsk. Sonia, another friend of my mother’s, also was also killed in Kamenets-Podolsk. My

mother graduated from music school and worked as a kindergarten music teacher. Actually, she had several

professions. She completed a short-term course for medical nurses in 1936 and worked as a nurse in

hospital for some time in 1936 – 1939. She also completed studies at an accounting school in the 1940s

and got a job of assistant accountant at the Tractor Manufacture and Sales Company.

Evel and Hanna Leibovich, my grandfather and grandmother on my father’s side (I have no information

about my grandmother’s maiden name), lived in Kuznechnaya (Gorkogo) street in Kiev. My grandfather

Evel was born some time in 1885. He was an intelligent man. I don’t know exactly what kind of education he

got, but during the Soviet time he worked as an accountant at a brick factory. I don’t know what he was

doing before the Revolution.

Leonid worked at a factory after finishing school. Later he studied at an institute and became an engineer.

Josif was a worker, and Rachel married Isaak Wainer and didn’t work after her wedding. All my father’s

relatives were evacuated during the war and returned to Kiev after it ended. Rachel died in 1972, and Iosif

in 1975. Leonid died in Kiev in 1977.

My father, Moisey Leibovich ,was born in Kiev in 1912. He only completed four years of primary school. He

didn’t study any further, but he was a very smart boy. Later he helped my brother with mathematics when he

was taking his entrance exams for the technical school. After finishing school my father, a 13-year-old boy,

went to work at Transsignal, the factory where his mother was working. He was a labourer at the beginning

and then he became a turner apprentice. My father was injured on the job before the war – the machine he

was working on cut off a finger on his right hand. My mother met my father in 1939 when she was in Kiev

on vacation. They met in a theatre in Kiev and fell in love. After my mother went back home to Kamenets-

Podolsk, they started writing letters to each other and my father traveled there several times to see her.

My parents got married in 1940, and my mother moved to Kiev. They had no wedding ceremony, they just

registered their marriage at the Registry office and started living together. My mother went to work at the

factory as an assistant accountant. My mother told me that she didn’t want to live with my father’s parents

and their family, so my father and mother rented an apartment.

The Second World War and the Shoah

The war began on June 22, 1941. At that time my mother was pregnant with me. The factory where my parents were working was converted to a military plant and promptly evacuated to Tashkent. My parents were evacuated with their plant. My father’s parents were also evacuated - but some time later. They also lived in Tashkent, but not with us. I remember that both of them died in 1943. My (paternal) grandfather died first and my grandmother followed him few weeks later. My parents lived with an Uzbek family. These people sympathized with them, especially with my pregnant mother. My mother had suffered very much during the long train journey to Tashkent. When I was born the doctors didn’t think I would survive. I was born with many lesions and bleeding sores. In fact, nobody believed that I would live, and the doctors didn’t want to take the responsibility for my treatment. My mother was discharged from the maternity hospital and sent home. But then our Uzbek landlords took over. The landlady went to her home village to see the healer. She brought back some ointment and herbs and they nursed me to health. So I owe my life to these Uzbek people. I don’t even know their names. I don’t know why, but after returning to Kiev my parents did not keep in touch with this family, but I remember that my mother always spoke with gratitude about their kindness and cordiality. My father went to work at a factory, and my mother stayed home with us kids. Later my mother also went to work, leaving us in the care of our elderly neighbours. Ours was a multinational courtyard – one could hear a mixture of three languages: Russian, Ukrainian and Yiddish. I remember that we were always hungry. There were ration coupons for bread. Sometimes my father brought lumps of sugar from his work that he got as food rations for the employees. We used to sit at the table and my mother broke these lumps in pieces, saying “Here is a piece for Zina, this one for Fima and this is for Daddy and Mummy.” Of course, those lumps for Daddy and Mummy were tiny, purely symbolic. My younger brother would eat his sugar quickly and then ask me to share mine with him. I felt so sorry for him that I would give him some of mine no matter how much I wanted to eat it myself. When my parents left for work, all that we had at home were onions and some bread. I used to cut a slice of bread, then I fried some onion with a little piece of pork fat and made a sandwich with this fried onion. Mummy told us to divide what we had, so when we ate we pushed some of the onion to the side, to leave it for the next meal. One of our neighbours had a vegetable garden in the yard, where she grew corn and various vegetables. We stole onions, carrots and cabbage from her garden and ate them raw to keep it a secret from our parents. We also stole corn and cooked in on the fire. Some people kept chicken, geese and even goats. Sometimes older boys caught a chicken and roasted it on the fire. I was scared to look at them killing it, but then I enjoyed having a piece of chicken when the boys gave me one. Of course, our parents had no idea about this “business” of ours. If they had found out it would have caused a terrible scandal, because they always taught us to be honest and never steal. But we were doing this because we were so hungry. Later we were sent to kindergarten. Our tutor was Musia, the daughter-in-law of my father’s brother Leonid. Life became easier in kindergarten, as we had meals there, even if they were scanty.

Moisey Leibovich - the

author’s father - 1937

with thanks to www.Centropa.org for permission to publish this material

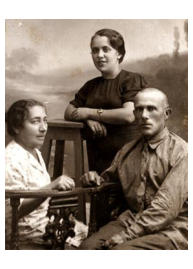

Zinaida Leibovich’s grandmother Haya-

Surah (died in Kamenets 1941), grandfather

Haim Altman, mother Shprintse Altman and

mother's brother Munya Altman 1932

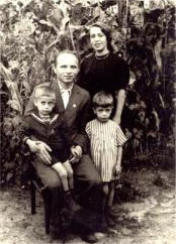

Zinaida Leibovich’s family: mother

Shprintse Leibovich, father Moisey

Leibovich, Zinaida Leibovich and

brother Efim Leibovich. Taken in

1946 after their return from

evacuation

The Impact of the Civil War

I don’t know any details of my grandparents’ life during World War I and the civil war. I don’t know whether there were any pogroms in their town – they never told me anything about it. What I do know is that my grandfather Haim Altman took part in the civil war and fought on the side of the Reds. I don’t know how he got to the front. He was there less than a year when he was wounded during one of the combat actions against the White Polish army. As a result, he lost his leg and returned home to Kamenets-Podolsk. This happened some time in 1918. Afterwards, as he couldn’t do hard physical work any more, he learned to make shoes and became a shoemaker in a shop. The family’s living standards dropped, but they didn’t get upset. They supported each other and did their best to survive. They continued to celebrate all the Jewish holidays and attend synagogue. On Friday my grandmother always lit a candle, and on Saturday her Ukrainian neighbour came to help around the house and take care of the poultry yard and cattle. My grandmother always made matzo at Pesach and even sold some to her Jewish neighbours. At home my grandmother and grandfather spoke Yiddish, and my mother knew Yiddish very well, too. My mother was born in Kamenets-Podolsk in 1919. They gave her the name Shprintse. The local rabbi issued her birth certificate, and we still have it. My mother went to a mixed kindergarten with both Ukrainian and Jewish kids in it. The teacher treated all the children very well. My mother told me that later she began to work around the house, helping her mother.

My grandmother Hanna, my father’s mother, was born in 1890. She didn’t work before the Revolution. In the early

1920s she also went to work at the factory. She worked at the turning machine. My father’s parents were

religious. They went to synagogue and observed the traditional Jewish holidays at home. Nonetheless, they

didn’t follow Kashrut and worked on Saturday, as it was a workday at the factory. Besides, it wasn’t possible for

Jewish people to be openly religious in Kiev in the early 1930s. That was why my father, along with his brothers

and sisters, was not a religious person. My father was raised in a very intelligent Jewish family. He had two

brothers and a sister. His older brother Leonid was born in 1907, his sister Rachel in 1917, and his younger

brother Josif in 1919. Neither my father, nor his brothers and sister got any Jewish education, and they did not

know and did not keep Jewish traditions; in their youth this was not fashionable and it was even discriminated

against by the authorities. But they always read a lot and learned a lot from people.

Click thumbnail to enlarge

Haya-Sura Altmann and

grandson Abram - both

killed in Kamenets 1941

Haya-Sura and Haim

Altmann (seated) with

their daughter Shprintse

Sonia - a family friend -

killed in Kamenets 1941

Genechka - a family friend

- killed in Kamenets 1941

Donia - a family friend -

killed in Lviv ghetto 1941

The Altmann family 1930’s

My grandfather Haim and grandmother Haya-Surah, my mother’s parents, stayed in occupied Kamenets-Podolsk and my mother didn’t know

anything about their fate. But at that time it was already common knowledge that the Germans left no Jewish people alive in the occupied areas,

and my mother had no hope of finding her parents alive. However, she kept praying for them and hoping for a miracle. But no miracle occurred. My

grandfather Haim and grandmother Haya-Surah Altman were shot along with all other Jews in town including their daughter-in-law, Uncle Munya’s

wife Fania and their three year old grandson Abrasha (Abram). We found this out after we returned from evacuation.

My younger brother Efim was born in Tashkent in 1944, and that same year, when he was only one month old, our family returned to Kiev. We

settled down in my father’s parents’ apartment in Gorky street, where he had grown up. It was a poor communal apartment, and our family lived in

one room. My father’s brother Josif and sister Rachel’s family lived in the room next door. We had another neighbour: Ida Kotlar, a Jew. They all

tried to support and help each other. When we arrived, our Ukrainian neighbours gave us some bed linen and furniture, as we didn’t have anything

at all. The toilet and water were in the yard. We cooked our food on kerosene stoves.

The 1950’s and 1960’s

I started school in 1950. It was an ordinary Russian school for girls. I remember the children teasing me. They called me “Leiba Muhamed – kerosinschik” instead of calling me by my name Zina. Leiba was from my last name Leibovich, Muhamed – because I had been in Tashkent (it is a very popular name in Uzbekistan), and kerosinschik – because we lived not far from and kerosene store. I took this teasing in my stride. But later, if somebody called me “zhydovka”, I found it offensive and ended any communication with those people. Quite often I faced anti-Semitism in my life, but it was at a later period, not while I was at school. We had a wonderful Russian teacher at school. She was Ukrainian and her name was Anna Vassilievna. She was the first person to tell us about Babi Yar. She asked whether we children, had any relatives that had been exterminated there. I asked my mother and she told me that every town or village in Ukraine had its own Yar [Yar in Ukrainian means a pit.] and that my grandmother and grandfather perished in Kamenets-Podolsk. This teacher was different from all the others. Nobody ever mentioned Babi Yar in those years – it was as if it had never happened. There was no monument or place where people could go to mourn for their lost ones. When I was 11, my mother and I went to Kamenets-Podolsk, my mother’s home town. It was a small provincial town, very clean and nice. There were hardly any Jews left - most of them were killed in 1941 and the rest of them moved to other towns. There was a small monument to the Victims of the Holocaust, and I found the names of my relatives on it. In 1953 Stalin died. I remember everybody around crying, and I cried, too, although I couldn’t understand or explain why, but as everybody else was crying, I couldn’t help crying either. Our family didn’t suffer from the “struggle against cosmopolitans” because we were very poor and nobody cared about us. Because of anti-Semitism, though, we couldn’t be allotted an apartment for a long time. We lived in terrible conditions. The Housing Department conducted numerous inspections to confirm that the conditions were bad and promised that we would get an apartment soon. But when the time came, it was always somebody else to get the apartment - somebody who was not Jewish. Nevertheless, we did move to another apartment in 1957. It was a communal apartment, too, but with a toilet and running water in it. Only in 1967 was my father allotted an apartment for the four of us. But although my father was an invalid of group I (he could hardly walk), we got an apartment on the fifth floor without an elevator! My father filed all kinds of requests to get an apartment on a lower floor. On the very day he died (in 1979) we received documents for an apartment on the 3rd floor. We didn’t move there, of course, as we were busy doing other things. My mother worked as accountant after the war. She became seriously ill after my father died and retired. She had cancer and was confined to bed for over 10 years. She died in 1990. I had to take care of her all these years and couldn’t possibly think about trying to arrange my own personal life. After graduating high school I wanted to enter the Institute of Culture. I passed my entrance exams but I didn’t find my name on the lists of those that were admitted. The administration explained to me that the reason was that my pass mark was not high enough, but the real reason was that I was a Jew. It took me a long while to find a job – as soon as people saw my name and nationality in my passport it turned out that there was no vacancy. Finally I found a low paid and non-prestigious job as assistant accountant at the Housekeeping Department. Later I took a course to become a “Variety Show Dispatcher” at the Institute of Culture and worked at the “Ukrconcert” (a concert agency in Kiev) as administrator for many years. My brother Efim Leibovich finished school in 1961 with excellent grades. He passed his entrance exams to commerce school but didn’t find his name on the lists. It turned out that a Deputy Minister’s son was admitted instead of him. My brother kept filing complaints with the Ministry and finally he was admitted. After he graduated, he entered the Department of “Refrigeration equipment” at the Institute of Commerce and Economy. Then he worked as chief production engineer for refrigeration equipment at the Kiev blood transfusion facility. He works there to this day. My brother has a family: a wife and two sons – Mikhail and Dmitriy.Jewish Support and a Jewish Identity in a Post-Soviet World

I have no family of my own. I had close relationships with a few men, but I never got married. When I realized that I would probably never get married, I decided to have a baby on my own. My daughter was born in 1983 when I was over 40 years old. Her name is Maria, Masha, and she is a very smart and beautiful girl. When she was in kindergarten she was chosen to study at a modeling school. She also finished the school of applied art and went in for gymnastics. Masha graduated from the Jewish school in Kiev and went to study in Israel under a program organized by the Kiev Rabbi Yakov Bleich. She has also been in America and visited the Lubavitch rabbi. He gave her $1000 to continue her education. Unfortunately, I deposited this money into a commercial bank, and this bank went bankrupt like many other banks in Ukraine in the 1990s. We lost all our money. Nowadays Masha is married to a Ukrainian man. He doesn’t support her interest in Jewish life and keeps her away from it. As for me, I feel my Jewish identity as never before. I go to the synagogue and services each Saturday. They have opened a synagogue at the Transsignal plant – the one where my father’s parents used to work. I’m so happy that the time has come when one can openly go to synagogue, study Hebrew and go to Jewish concerts and performances. I try to read Jewish newspapers. I go to the Hesed Jewish center “Hesed” where I can get charity meals and other assistance. Sometimes I hear anti-Semitic statements in the street, but this happens rarely and doesn’t feel as offensive as it did before, when we couldn’t lead a Jewish way of life and heard such statements about Jews everywhere: in the traffic, in stores or in the street. Everyday expression of anti-Semitism still exists, but it has nothing to do with state policy and I hope there will be no more anti-Semitism in Ukraine. Unfortunately, I have never been in Israel. It was impossible in the past, and then, when they opened the border in the 1990s I never had enough money for the trip. I would love to see this country and visit its holy historical places. Zenaida Leibovich’s testimony as told to Zhanna Litinskaya of Centropa.orgSurviving in Soviet Russia

This is a biography of a Jewish family, partly originating in Kamenets and partly in Kiev, during the 20th century. It was told to a researcher working for Centropa.org in 2002 by Zenaida Leibovich and is a graphic description of life in the Ukraine; with important information about survival and death of Ukrainian Jews. It also provides some further details of the ending of the Jewish community of Kamenets. I was born on January 30, 1942 in Tashkent, Uzbek SSR. My parents were in the evacuation there during World War II. My father’s name was Moisey Evelevich Leibovich and my mother’s name was Shprintse Haimovna Lebovich (nee Altman). My grandparents all died before I was born, but I heard a lot about them from my parents.

Munya Altmann became a professional

soldier. “When World War II broke out in 1941

he held the rank of lieutenant and was sent to

the front. He went through the whole war and

finished it as a major. His wife Fania and son

Abrasha, who was born in 1938, stayed in

Kamenets-Podolsk and were shot by the

Germans in 1941. Their bodies were thrown

into a sewer. “

From Zenaida Leibovich’s testimony